What is the cost of doing business?

Compliance cost accounts for an estimated 21% to 33% of the gross development value (GDV) in townships.

Overregulation and inefficiencies lead to higher costs in housing projects

By Yanika Liew

When it comes to the cost of developing property, construction, material and labour cost comes to mind but few people understand that a significant portion of the cost is the compliance cost, also known as the cost of doing business.

“The cost of doing business is very difficult to demonstrate to the state government, without us knowing how to break it down, so they understand,” Sime Darby Property Bhd group managing director Datuk Azmir Merican said.

According to the Real Estate and Housing Developers’ Association (Rehda) Institute Housing Forward 2022 report, compliance cost accounts for an estimated 21% to 33% of the gross development value (GDV) in townships, with 12% to 35% of the GDV in strata developments. It remains one of the greatest challenges to affordable housing.

The report defined compliance cost as the expenditure of money and time conforming with government policies, legislation and regulation. Developments have a long gestation period spanning five to six years, and the costs include the reduction of sellable land, approval delays, regulatory fees and more.

In developments, a certain percentage of land has to be set aside for public facilities, roads and drainage, open spaces and parks, as well as utilities. These facilities include hospitals, schools and other areas. There are also payments to various government agencies pertaining to electricity supply, water piping, telecommunication connectivity and sewerage systems.

These utilities used to be provided for by the government, but with privatisation, the cost fell on the developer.

“You surrender land, you have less area to build,” FIABCI World Council of Developers and Investors president Datuk Seri Koe Peng Kang said.

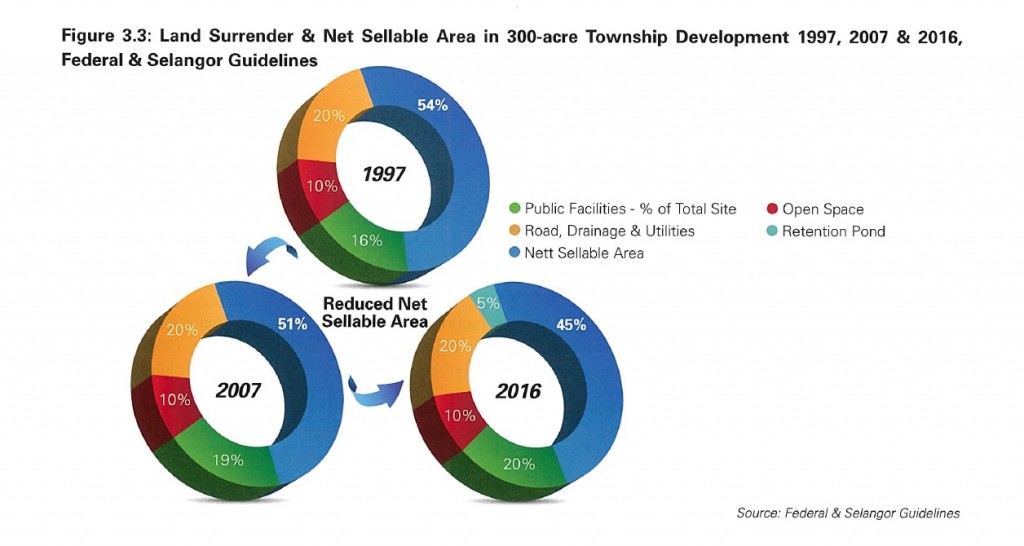

Throughout 1997, 2007 and 2016, the net sellable land per project gradually decreased from 54% to 45% of the total land area.

“We give land for schools and dewan. Now [some authorities in Selangor] are imposing that we build the building itself, including schools,” Glomac Bhd chief operating officer Zulkifly Garib said.

He pointed out that even if the state did not need a new school building, they would ask for a contribution.

The communication between government departments also needs to be more efficient, Gamuda Land chief operating officer Wong Siew Lee said.

“Just sharing a scenario, there’s so much school land we need to surrender, and our neighbour [another developer] are also surrendering school land… All the school land is just clustered together at one place. When we go to MOE (Ministry of Education), they don’t even know that the land has already been surrendered to them,” she pointed out.

This lack of communication led to several sites being allocated for the public, only to be overlooked and left undeveloped.

In a similar vein, Rehda president Datuk NK Tong pointed out the case of a particular housing development in Selangor, which had been allocated 20 school sites. To this day, only two have been built.

“So what happens to the other 18… That is money the rakyat has paid for, that are idle assets not producing,” Tong said.

Housing development involves a complex approval process involving federal, state and local authorities as well as other additional agencies. According to the Rehda Institute, this meant the entire process could take anywhere between 67 days and 272 days, leading to exorbitant holding costs.

There was a consensus among developers that the policy itself had to be streamlined.

Matrix Concepts Holdings Bhd group managing director Ho Kong Soon recalled an instance with Matrix’s industrial park, where a consultation with the power management unit (PMU) would require a large payment with a price in the millions, as well as an extended period of waiting.

“They say, want to consult PMU. I need four years, my goodness, my inventory waits for four years?” he asked.

Currently, a lot of negotiation and networking is required to expedite the process, Ho said. However, he pointed out that a healthy and conducive business environment required clear policy, rather than constant back-and-forth.

“These are the [projects] that you build as a catalyst, for the locals, for the state, for the people, everybody must put their effort inside to make it a success,” he said.

The issue of cross-subsidies

The cross-subsidy model is unique to Malaysia, where affordable housing units are funded partly by open market units. These open market units are priced to bridge the gaps between the price and cost of developing the affordable unit.

The issue is when these affordable units are left unsold, yet remain unreleased for sale in the open market. When it comes to bumiputera units, the cross-subsidisation and release process of affordable units is a similar one.

Bumiputera unit buyers have to hold onto their unit for five to 10 years before the unit can be sold. Due to this, a majority of bumiputera home buyers would rather invest in non-bumiputera units, leading to unsold, unreleased units.

Sabah is the first state in Malaysia to change this policy with a people-driven solution.

“In a nutshell, a bumiputera investor comes into your sales gallery. [Out of] the 100 units, they can point at any of the units. They actually will be offered – any of the ordinary units, not bumiputera – but we are giving them the 5% discount, regardless,” Sabah Housing and Real Estate Developers Association (Shareda) managing director Datuk Chua Soon Ping said.

With this, bumiputera home buyers would retain their discount while being able to buy and sell their homes as regular units.

A survey by the Rehda Institute found that 46% of the respondents’ unsold quota units have been in the market for more than 36 months and 30% are unsold and unreleased beyond five years.

Approval for release is subject to various eligibility criteria by each respective state, and developers call on the government to implement a standard release mechanism.

As the net sellable land decreases while the cost of housing increases, developers find that the price for these units will only continue to increase, causing projects to be unsold and eventually abandoned.

“Just to be clear, this is again state by state. So KPKT, they have a very uniform policy but it’s not followed by the states,” Tong said.

“I think YB Nga has asked Rehda and we have given him all the different compliance requirements that vary from state to state and he wants to engage the state authorities to harmonise and standardise but again it really is up to them.

“Hopefully they are in the position to be able to use their influence to at least streamline a lot of these policies with the goal of making things more affordable,” he said.

We want to standardise and expedite the process of authority approval and timeline because the delay costs a lot of money, Koe agreed. This would increase overall efficiency and enable developers to hand over projects promptly.

“I think what people don’t realise is we have to have a very resilient industry… and resilient means there must be a reasonable amount of buffer. Some people call it profit, buffer (But that is) to withstand some of the headwinds that are coming,” Tong said.

Source: StarProperty.my

POST YOUR COMMENTS